Soon after these encoutners[1], he started his musical career as DJ Balli and launched his label, Sonic Belligeranza in 2000. To this day, the label is releasing wildly experimental, conceptual and often controversial music while DJ Balli continues to perform regularly (recently and prominently alongside Zombieflesheater and DJ Scud at Milano’s Macao). At the end of the nineties, Balli started writing books and making contributions to anthologies such as Rave in Italy.

Benedikt Achermann visited the Bolognese artist in his semi-formal shop (a story unto itself…), located in the back of a bar on Via Mascarella in Bologna. They talked about the breakcore state of mind, gabber’s resurgence and Balli‘s book project on gabber futurism.

Benedikt Achermann You just got back from a trip to Vienna, right? What were you doing there?

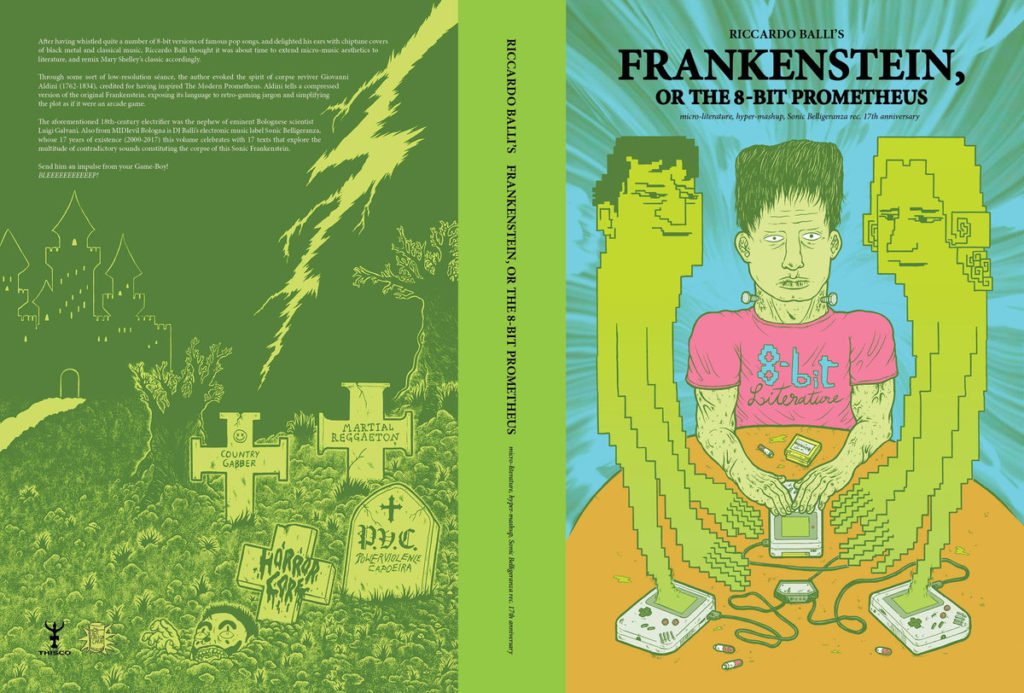

Riccardo Balli This time, I was there for a presentation of Frankenstein, or the 8-bit Prometheus [Chili Com Carne editions, 2018] at Buchhandlung im Stuwerviertel. It was on invitation by Rokko, the editor of Rokko’s Adventures, a kind of “Wasted Jugendstil” magazine dealing with Vienna, literature, and music. Frankenstein, or the 8-Bit Prometheus is my first book in English and was published in April 2018. At the presentation, I was joined by Bianca Ludewig, who has just published her study “Utopie und Apokalypse in der Popmusik: Gabber und Breakcore in Berlin”. On Saturday night, I played the “Lauter Lärm” party at Venster 99, where I’m sort of a resident act. The party focuses on hard electronics, bridging the gap between harsh noise and extreme dancefloor sounds. Istari Lasterfahrer and The Massacre of Swiss label Terrornoize Industry also played.

BA You were right there at the beginning of breakcore. Are you still following breakcore these days? How do you see the current state of the genre?

RB Breakcore, to me, always has been primarily a hybrid strategy. I clearly remember that around 2004, I got the impression that the genre developed into a codified style. The style’s formula combined gabber kicks and amen breaks. I saw this pattern being repeated over and over again—and it bored me. In a bigger historical perspective, breakcore was nothing new. Avant-garde movements have traditionally been about the juxtaposition of things that don’t fit—clashing and mashing and seeing what happens. This is the attitude I wanted to keep. Therefore, I started to look for ways to take the breakcore strategy outside of music and into other projects. My Sonic Belligeranza label was always oriented towards hard dancefloor sounds. Still, breakcore started to give me this claustrophobic feeling. As a reaction, I started the -Belligeranza and +Belligeranza sublabels. The latter is used for harder sounds and conceptual noise projects. The former deals with softer fare. The music released on -Belligeranza ranges from battle breaks (records made for scratching), to underground horrorcore hip hop, to vaporwave. It’s weird stuff for sure, but not so much about “hard” sounds. It is rather about expressing cutting edge ideas. I see the way that I write as a way to apply breakcore as a strategy to projects outside of music. Frankenstein, or the 8-Bit Prometheus is a literary mash-up of Mary Shelley’s classic, taking influence of 8-bit videogaming culture and contains non-fictional accounts on occasion of the 17th anniversary of Sonic Belligeranza. I did not want to write this as a classical essay, but was aiming for a mix of literary and low-brow styles.

BA A lot of Sonic Belligeranza‘s output is highly conceptual—something that’s not often seen in hardcore electronic music. It seems like you’re quite comfortable moving between low brow and high brow culture…

RB Yes, “conceptual” is something that is often used to describe my work. I’ve been into noise for a long time now and to me most of it is boring and predictable. I try to refresh the noise scene with ideas. One of Sonic Belligeranza’s best records for example features noise made by skateboards[2]. Or there’s the Quattro Stagioni pizza noise record[3]. It comes down to breakcore again—on a conceptual level, I try to be breakcore in life. Mixing high and low brow not just in music, but in life. Historical avant-garde movements were always about bridging the gap between art and life. Art is not art if it is separated from life. Art is a form of direct action.

BA It‘s fascinating to see how Marc Acardipane‘s cryptic catchphrase “see you in 2017” played out. The last three years have seen a renewed interested in nineties rave culture and along with it the gabber continuum. Collectives such as Paris’ Casual Gabberz [see zweikommasieben #16] and artists like Sentimental Rave, Hdmirror [see zweikommasieben #19] and Italy’s Gabber Eleganza [see zweikommasieben #17] have picked up the sound and aesthetics of the culture. All of the mentioned artists play Berghain these days. Meanwhile, Thunderdome celebrated its 25 year anniversary with 40 000 ravers. Furthermore, the underground hardcore scene seems to be revived as well, with Praxis Records celebrating its 25th anniversary. What do you think about this gabber renaissance?

RB I’m really happy about it, probably in opposition to other gabbers my age, who dismiss this new wave as “hipster hardcore.” There is some truth to that, but overall I think it brings light to a phenomenon that deserves more attention. Gabber is important for electronic music. A lot of gabber‘s sonic solutions, such as the hoover bass and the attention given to kickdrums, influenced electronic music in general. I see gabber as electronic music‘s equivalent to punk and metal, opposing techno as punk did (prog) rock.

BA This opposing stance or subversive potential of gabber comes up a lot. How so?

RB Personally, I am more interested in subverting gabber itself. The genre is often dismissed as idiotic music. I want to parallel it with a really high-brow, avant-garde movement. In this case, the Italian futurist movement.

BA That’s the subject of your most recent book sbrang gabba gang! released by Agenzia X, right?

RB Yes, its subtitle is “The Gabber Reconstruction of the Universe”, my take on ricostruzione futurista dell’universo, the manifesto by two Italian futurists from the early 20th century, Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero. I can see many common points shared by gabber and futurism. Both movements worship velocity and share an aesthetic of war and belligerence. Both were accused—often rightly so—of being fascist. I went deeper into these parallels and this is what sbrang gabba gang! will be about. Again, I’m following an approach that mixes fiction and non-fiction. This time I’m messing around with futurism instead of the Shelley classic. As an example: There’s the famous text “The Art of Noise” by Luigi Russolo, which I’m reworking into “The Art of Bassdrum”. The fictional part on the other hand follows the adventures of a posse of gabber futurists. They deal in “art vandalism,” damaging Italy‘s art heritage. I’m going back and forth between fiction and non-fiction, between gabber and futurism, mashing them up. In a way, I want to vandalize futurism by introducing gabber to it.

BA Art vandalism? Tell me more!

RB The futurists wanted to destroy the museum. There’s a fascinating case I’m studying about a guy who took this very literally, Piero Cannata. He’s notorious for a series of acts of damaging artworks. In 1991—and this is only the most famous case—he took a hammer to Michaelangelo’s David. Cannata is currently in a mental asylum. This resonates with my idea of gabber futurism. Gabber is traditionally linked to hooliganism. When the Dutch team plays Rome, they always leave a trail of damage… Fashion is another parallel. Fashion was very important to both gabbers and futurists. The futurists wrote all kinds of manifestos, about food for example, and also fashion. The tracksuit was actually invented by futurists! Two Italo-American-Swiss brothers came up with the original design in 1919. I‘m spinning a fictional trajectory from there to an integral part of the gabber uniform: tracksuits made by the Italian brand Australian. Futurism is something that is studied in public schools in Italy—in a way it’s quite “pop.” Even teenagers know about it. I hope to create a better understanding of gabber and also offer new perspectives on futurism. Many refrain from going deeply into it, because of its murky politics and its links to fascism. Not all of the futurists were fascists, but there were connections. It’s important to contextualize what fascism meant and what it’s role was at the beginning of the last century. Nevertheless, it is an accusation that cannot be ignored and has to be discussed. Some futurists clearly were fascists, such as Filipo Marinetti, author of the futurist manifesto. I refer to him in my book as ‘Dominator’ Marinetti, making fun of his role as the undisputable leader of the movement.

BA Dominator of course being the name of the massive mainstream hardcore festival in the Netherlands…

RB Exactly. To mention another example of how I dealt with the issue of fascism: The already mentioned Balla not only wrote the manifesto but also was a famous futurist painter—and had a fascist period. Deleuze and Guattari write about biological fascism and “micro-fascism.” In each of us, they say, there is an element of fascism. So, let’s deal with that, subvert it! I’m doing this by way of alliteration, from Balla to Balli—and bring it to a personal level, for example on my tape Svelto The Hakken Tuner for Arte Tetra.

BA A reaction to gabber—also in my personal experience—is that people still very much see it as “Nazi music.”

RB It’s the same in Italy. There are good reasons for having such a view, but I think it is mostly rooted in ignorance and not really knowing about gabber. I see gabber as an expression of working-class, lumpenproletariat culture. It’s a very similar story to how within the punk movement, the oi and skinhead subcultures were subverted by the extreme right and to this day suffer from this association. That‘s something I deal with in my text “How To Cure a Gabber.” I’ve been around gabber culture since the nineties and in this text I analyze and share some of my experiences. I was playing mostly breakcore in the nineties. The squats I usually played in Italy weren’t into it. They were playing a lot of drum’n’bass and didn’t understand this sound. “It is all distorted! You should learn how to mix!” they would tell me. At the same time, I got bookings at commercial gabber events. I met people there who really enjoyed my music—but had political views that completely embarrassed me. I still sell records and books at parties these days. In the nineties, this was a way for me to interact with “real” gabbers. I was often confronted with right-wing and racist attitudes. My impression was that these attitudes were in most cases just simple-minded ones, just people following what their peers were doing. In some cases, I managed to find common ground with them in the musical interests we shared. I told them about artists like The Darkraver or DJ Loftgroover, people of color, or Liza’n’Eliaz, an influential trans/queer gabber artist. This was my way of challenging them, planting doubts about their views into their minds. I’m not saying that this approach was 100% successful. But in some cases, I had gabbers following me to anarchist squat gigs, where they were exposed to different ideas. Had I refused any contact, in an orthodox Antifa way, or tried to fight them, none of that would have happened.

BA Oddly enough, the extreme right is appropriating the Antifa look these days and are even reworking slogans such as “good night white pride” into “good night left side.”

RB And in Italy we now have right-wing squats by a movement called “Casa Pound.” Once again, there is an example of far-right movements appropriating culture and tactics developed by the left—in this case the strategy of squatting. So, let’s get it back! sbrang gabba gang! is a statement for re-appropriation of a culture that “belongs” to us. It‘s an act of reclaiming gabber culture, as I don’t think gabber is right-wing. Gabber doesn‘t carry a political message. Gabber is music for partying hard and can maybe serve as a valve to deal with a tough working-class existence. This is another thing gabber and futurism share: aggression, toughness. At Number One, a discotheque in Brescia, at the end of the nights there was the famous “gabber pyramid.” It’s Italian gabber folklore by now and you can find fascinating footage of this on the web. Punters were meeting in the centre of the dancefloor and created a human structure, climbing on top of each other. The goal was to reach the top and to touch the ceiling of Sala Due. It was a form of violent dance, a moshpit of sorts. Futurists meanwhile would hold soirées, nights of poetry readings and showcases of futurist art. These evenings incorporated deliberate physical provocation, an overall belligerent attitude. Quite often, these soirées ended in riots. Umberto Boccioni, a futurist painter, documented this in his painting “Riot in the Gallery” from 1909.

BA Simon Reynolds and Mark Fisher, may the latter rest in peace, often mentioned experiencing a kind of “future shock” upon first hearing jungle. According to them, such a future shock is becoming increasingly rare. When is the last time you have experienced a kind of future shock upon hearing a new development in music?

RB I’m constantly looking for this kind of shock. Searching for and investing such shocks is the point of my label. Recent moments of shock for me were death rap, horrorcore and extratone. Whenever I find something that strikes me as interesting, I try to make a record about it. With Rancid Opera, we explored horrorcore rap, using the language of Opera—which traditionally has some gore elements to it—to mock shitty Italian rap. Extratone with its 1000 beats per minute (and beyond) is another example of this, we’re one of the few labels that actually have released this style on vinyl. In a way, that shock you asked me about keeps me psychologically balanced. I’m always looking for new shocks, for new sonic Frankensteins. This curiosity for new concepts and ideas keeps me going and I still have a lot of fun investigating them.

This interview accompanies another text featured in zweikommasieben #19, where Benedikt Achermann—alongside Moritz Weizenegger—had a chat with Hdmirror to look from another angle into a current resurgence of hardcore inspired music.

The pictures of Balli were also taken by Achermann.

[1] Documented on prole_sector‘s Instagram.

[2] In Skatebored We Noize (+Belligeranza 04)

[3] 4 Seasons Pizza (+Belligeranza 05)