Born in Malaysia, Tzu Sing Tho aka Tzusing’s adolescence was split between Singapore, Taiwan, China, and the U.S. He manifested a sound that abandons the limits of typically rigid techno and industrial music to incorporate more harrowing ornaments derivative of his East Asian roots. Now based between Taipei and Shanghai, Tzusing is a producer and DJ that has found a more permanent home on PAN and L.I.E.S. Records, where he’s released a trilogy of 12″ via the A Name Out Of Place series, alongside his formidable debut album 東方不敗. On 東方不敗 (Dongfang Bubai), samples of traditional woodwind instrument and hammering drums emulsify to soundtrack the relentless rise and fall of power amid a battle between confusion and madness. With a new album set to be released on PAN and a label in the works, Tzusing isn’t slowing down anytime soon. Claire Mouchemore caught up with the artist for zweikommasieben. Their conversation touches on traversing from West to East and vice versa, listening to music without prejudices and how a pair of possibly stolen Technics turntables kickstarted his interest in DJing.

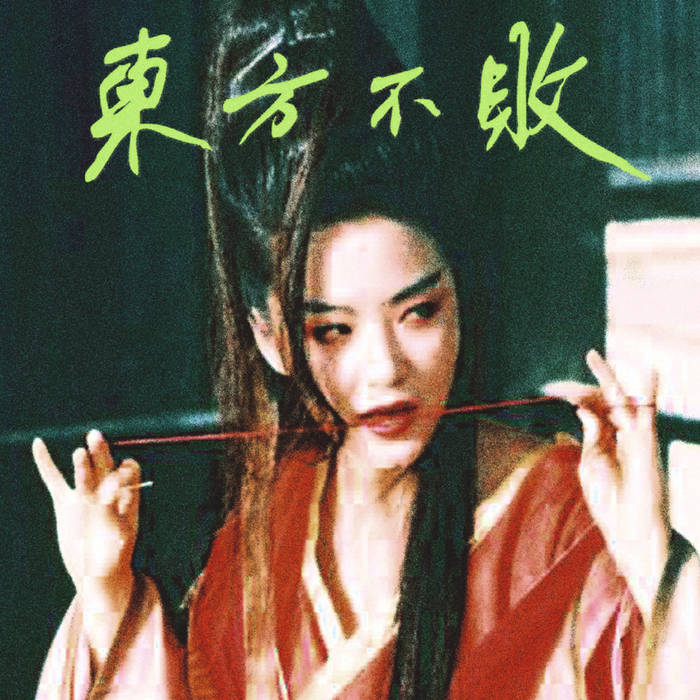

Claire Mouchemore During your set at Supynes Festival back in 2019, a pair of eager hands grasped a copy of your debut album 東方不敗, waving the record high above the heads of those in the crowd in what seemed like an attempt at a song request. Although your set took an entirely different direction, that record remains the pinnacle of your discography. The story behind the genesis of those seven tracks, however, isn’t all that well known. The release depicts Dongfang Bubai, a character in Jin Yong’s novel The Smiling, Proud Wanderer: a tale of a man who must sacrifice his masculinity via castration. In the story, this act of surrender is said to achieve the ultimate level of power. What significance does this character represent in your life?

Tzu Sing Tho I think I was in the fourth or fifth grade when I began to watch the film adaptations of Jin Yong’s novels. My folks weren’t big into music, but they were into film, and we’d often watch those movies together. I was instantly drawn to the character. I found them to be visually entrancing. In the book, the character Dongfang Bubai is represented as a man, whereas in the film, the character renders more feminine qualities. Her weapon is a mere needle and thread, which she uses to fight her opponents that are armed with heavy chains and enormous claws. The difference in weaponry seems quite unfair. I always liked this idea that being the most powerful isn’t always the most obvious thing. It isn’t always the big burly macho dude that holds the strength. It can look different. I’m very into these ideas. Everybody likes the David vs. Goliath story, right?

CM Your music seems to be favored equally, if not more, by European audiences—a fact that is reflected in the success of your debut album. Western society has a tendency to consume Asian culture in ways that often fetishizes heritage, playing into obsessions with particular cultural aesthetics. How do you navigate these perceptions through your output as an artist? You’ve noted previously that it’s something that conflicts you…

TST: I’m not going to lie: I definitely think about it. I’d like to not think about it. When it does cross my mind, I realize I’m giving that Western perspective so much weight and power just by worrying about how things will be perceived. At the same time, I have friends telling me that I should worry, that I have a responsibility to consider how things are perceived. I’m constantly considering how people will interpret things and whether it will be in the right—or at least intended—way or the wrong way.

CM To a degree, the responsibility should fall on the listener that’s engaging with the music to consider how they’re perceiving the work, not entirely on the person that’s crafted it.

TST That’s a nice way to look at it. I have friends that have different perspectives on that for sure.

CM Were you met with criticism from certain people after the record was released?

TST Some friends accused me of cashing in, saying that it was an easy cover to do, to have an Asian woman front and center. In reality, I’ve been very obsessed with this character for a long time, and it completely lapsed in my mind that it would be perceived in a certain way outside of Asia. I also know, though, that people clicked on the album just because of the cover. It was baity, which wasn’t my intention. My previous records did well, but they didn’t get this kind of attention. L.I.E.S. is still an underground label, and doesn’t do so much to try and get things out there. I didn’t think people would notice and that it would have such a snowball effect.

CM As you said, the character has held great importance for you since you were a child. You shouldn’t have to limit what you include in your work, depending on how other people choose to recontextualize things.

TST Or should you? That’s the eternal question. We’ll never know. Some friends say it’s the artist’s responsibility; you should care and consider all possible scenarios. But it’s so much to think about, and you can subdue yourself in a lot of ways. Okay. I really want to say this. I think I once said in an interview that I feel like I’m appropriating my own culture because I have a problem with people discussing cultural appropriation in such a basic way. Here is what I want to ask people: at what point do you own your culture? At what point are you the spokesperson for your culture? I know so little about my own culture. Of course, I know more about China than the average Western person, but I don’t know that much about Chinese history or Chinese culture, and I would never dare to say I own this and you can’t use it. That feels so weird. Who has the right to say that unless they’ve studied it at length and have this crazy knowledge of the full extent of the history and culture that accompanies it? Then and only then can you start to make these statements. Before that, it’s kind of strange to feel like you completely own it. I don’t think that really answers your question, though.

CM Not entirely, but it loops back around to something else I wanted to discuss. You were born in Malaysia and grew up between Singapore, Taiwan, China, and the U.S. You moved around a lot, almost constantly. On the subject of communicating cultural heritage and posing as a spokesperson for certain cultures: figuratively, where have you settled after being exposed to so many different societies and upbringings? Do you harbor a desire to belong?

TST I don’t feel the need to belong. If you want to put things in that way, then yes, I don’t know where I belong. I also kind of don’t care. The way the world is moving right now, the need to belong in the sense of national identity will hopefully soon become obsolete.

CM In a previous interview it was stated that during your high school years, you smashed a classmate’s guitar in a revenge-driven rage one lunchtime, and as a result, your parents sent you away to live in China. Was this indicative of your feelings towards guitar music?

TST I was trying to make a statement. He was saying stuff behind my back, so I wanted him to know that it was me doing this to him out in the open. It was an electro-acoustic guitar, so it had a big holo body, perfect for smashing in the school plaza in front of everyone. The school was like: “there’s something wrong with this person.” And my mum and dad thought I was going to become a Triad member or something.

CM And that time in China, it was almost impossible to get access to turntables, let alone records. Did relocating to the U.S. provide you with greater access to electronic music?

TST I was into electronic music even before I arrived in the U.S. The first time I heard it was in the seventh or eighth grade. I went to an international school in Taichung, and there was a kid from the States in my brother’s class. He was a few years older than me and had a sister that was a raver. He’d just moved from Dallas and had these rave CDs that his sister had given him. He let me listen to them, and I was like, “holy crap, what is this?” It was mostly mixed CDs, comprised of Josh Wink, The Prodigy, and Bad Boy Bill. Even some goth and new wave stuff, a lot of hard house mixes too. I was super into all of it. There wasn’t a stigma around these genres. I didn’t know the context of the music. I didn’t know anything about it. I was taking it all in on a purely sonic level. I didn’t know whether it was cool or not cool or what kind of person was listening to it.

CM That’s such a gratifying way to immerse yourself in music: without context, lacking prejudice.

TST When I moved to the States towards the end of high school, I knew that I’d be surrounded by music. As soon as I got off the plane, I tracked down a pair of turntables on Craigslist. I’m pretty sure the guy stole them, and was trying to move them on as soon as possible. I was thinking about turntables when I was in China, but they were insanely expensive, plus there were no record stores back then either. That’s still kind of the case now because there’s not a lot of people buying dance music vinyl, so there’s no reason for record stores to stock the stuff. There weren’t a lot of DJs there at that time, so it didn’t warrant a proper record store. Although, a friend in Taichung was already running a record store in the mid-late 90s. He could only stock so much stuff, though, even a bit of techno; however, people weren’t really buying it.

CM Had you used turntables before you got a hold of your first pair in San Diego?

TST A little bit… I had some friends who were DJs that would let me screw around on their stuff. There were a lot of CDJs around in Asia at that time, CDJ 100s and 500s, before the CDJ 1000 was out. There would always be a pair of CDJ 100s at house parties, so I would mess around on them there. I would trainwreck every time; it was pretty embarrassing. But I just wanted to give it a try. When I’d been on visits to the states before moving, I would go to record stores and buy vinyl to bring back to Asia, even though I didn’t have turntables. I just wanted to own records and music in general. On one trip, I picked up a Goldie CD, Sasha & John Digweed mix CD, and an Aphex Twin vinyl. I was quite into collecting trance records too.

CM You’ve been DJing for seventeen years, acquiring your first pair of decks from a Craigslist ad upon arriving in San Diego in the early 2000s. A lot can change in seventeen years, from DJ style to selection, depending on the evolution of taste, sound, and space; from your first gig at an Irish pub in Chicago in the mid-2000s to the warehouse show you played in Melbourne, Australia, in 2018. What have you learned from playing to crowds across the world throughout all those years?

TST I don’t play Europe that often, but when I did, it was at either CTM or Unsound. During those first few shows, it was this time before I started taking my selection in a different direction. People showed up expecting a techno set, but I switched to playing full-on footwork halfway through. The crowd was a bit like, “what are you doing?” But right when I got off stage, Bill Kouligas from PAN was looking at me like, “what the fuck did you just do? That was insane.” He was always super supportive. In 2015 I saw Air Max ‘97 play at Shelter. He was able to take the internet stuff and play it cohesively, blended with some older, more classic tracks. He really switched up my way of thinking and DJing. I was playing a lot of techno and new beat before then, and hearing him play inspired me to change the way I approached DJing.

CM For many, former Shanghai club The Shelter was an institution that facilitated an ever-changing roaming of musical discovery. Before its closure, did that space hold a similar sentiment for you?

TST The government is cracking down hard on culture, and it’s not looking promising for Shanghai. A lot of venues are closing. The closure of Shelter alienated a lot of the proper house and techno people that used to go there regularly. That crowd has since migrated to All club, which is appealing to a new generation of Chinese kids that don’t find house and techno interesting. They’re pushing newer styles of music. Shelter was mimicking something that had already been done, and I feel that All is something that we’ve never seen before. I used to be there every weekend when I was in Shanghai. Obviously, the space at Shelter is unparalleled. Shelter was a literal bomb shelter that you’d enter via a tunnel and a place where noise restrictions weren’t a thing.

CM You hinted that All is pushing more experimental styles of sounds. More specifically, how does that space differ from other clubs that have come before it?

TST There’s a community of people going out. Fashion is taking off. There’s no judgment on how you look. I think that’s one of the most significant differences I feel between Europe and Asia: people don’t worry about looking normal or DJing normally in Asia. There’s no normal. There’s no standard, and when you take that away, you’re left with infinite possibilities. But that comes with its own set of problems, such as a lack of technical ability. That’s the other side of it. Having rules is sometimes useful to maintain this technical proficiency. You lose some, and you win some. All club is run completely by local promoters, Chinese promoters, besides the club owner who is British and used to run and own Shelter.

CM You’re always in pursuit of new ventures in and outside of music. Besides running a successful manufacturing business and spending your downtime skating through the streets of Taipei, what’s on the horizon?

TST I’m starting a label. It’s called Sea Cucumber. I have a few releases ready to go that I’ve already been playing out for a while now. The first record will be coming out in two months. The label won’t be Asia specific: I plan to release a lot from producers based in the UK, France, South America, and so on. A lot of the people are from SoundCloud and I’m hoping this label will give them the platform they deserve.