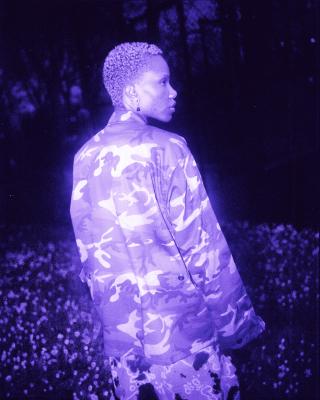

Some of Us Had to Get Free, and Some of Us Might Tygapaw

Tygapaw

Photography

Avion Pearce

“The ground shifted beneath her feet. Could she move them as well? It had been hard to get the others to hear her out initially. She felt instead, release. Some of us had to get free, and some of us might. This liberation feels like a crush. My heart is hurting. She thought, I’d want it more than anything. She thought. She played out the serenity there before, sun drawn to her skin, like a magnet, like a knowing, like an old friend. The salty preserve on her brow. Running, running across her mind. Clean like a mine. She could taste that serenity. Her blood sugar dropped. It aches to know. And yet, there was a pleasure to the stepping through it. The liberation feeling the ground crunch. My heart is racing. She thought, I’d want it more than anything. She thought.”

Mandy Harris Williams’ text evocatively introduces the first track of Tygapaw’s 2020 album Get Free, released on the N.a.a.f.i. imprint. Originally the album’s intent was to reject self-doubt, but it gradually grew into an exploration of personal liberation and self-discovery as an integral process. Earlier in 2020, Tygapaw released a three-track EP titled Ode to Black Trans Lives: an unmistakable call to action and in many ways an extension of the Fake Accent club nights in Brooklyn they have been organizing since 2014, igniting spaces dedicated to queer Black communities, and now used as a label as well. zweikommasieben editor Helena Julian spoke with Tygapaw about how these two recent releases resonate with each other, the significance of spoken word in music, and perpetually thinking through the body when creating.

This interview was originally published in issue #23.

Helena Julian

Looking back, it seems like one thing we opened up to globally in the last year was the act of listening to each other, to witness someone’s experience. Your two most recent releases seem to echo each other in a way, both giving an account of a political stance. Could you tell me more about the conceptual process behind these two and what your working conditions have been like in this pivotal year?

Tygapaw

Ode To Black Trans Lives was an immediate response to the Black Lives Matter movement. It was a way of responding to the Black community as a whole having a lack of attention to Black trans lives. Justice is rarely served towards incidents and cases often go unsolved. There is an overall issue of transphobia. I found a lecture of D-L Stewart speaking about issues of transness and the right of having autonomy. I really connected with this lecture, so I wanted to put it in a musical composition. I often work with another piece of work that inspires me. I made two of the tracks on that EP in one day and I added a track that I had done at my Pioneer Works residency. I layered it with D-L’s words, responding in a more emotional way to my thoughts.

Get Free was more long-term research. I started intentionally thinking about my culture, Maroon culture. It is a very isolated community within Jamaica. So unless you’re invited into that community, you can’t really get in. I bought a whole bunch of books, and during the pandemic things shifted for me. I was more inspired to create something with the intention to celebrate ourselves in regard to Blackness. Originally it was about overcoming self-doubt, but it grew into talking about a more emotional state. I want to draw the listener into my experiences. When I listen to it now, it sounds like an opera to me, like I made a soundscape to techno. I have plans for it to become an opera over time: a Black techno opera.

Helena Julian

The works seem relentless and full of intent. Perhaps they provide less a space for contemplation but instead create a space for action. Many of us won’t be able to listen to this in the closeness of our communities at the club yet. How do you hope this reaches people?

Tygapaw

The challenge is always to make techno accessible as it’s evolved to something that exists in a particular space. I always like music to be boundless. It’s about the initial response to the sound. It’s wherever it reaches you that becomes important. I’m interested in music that can come to you as a whole, so you feel satiated at the end, and that there is a completeness to it as a body of work. DJing contributes a lot to the way I make music, especially in regard to the intensity of the sound. I would love for it to be presented in a live setting.

When I made Love Thyself [Sweat Equity NYC, 2017] I wanted to see it as a whole, but the confidence wasn’t there to make everything into a cohesive project. The EP Handle With Care [Fake Accent, 2019] was the moment where I was ready to propose each project as a full body of work. Handle With Care was about facing generational trauma, family dynamics, and my heritage. As I grew up in Jamaica, there is a lot of complexity with the challenges we face through the after-effects of colonialism. Music has been the thing that has guided me. It’s been that solace and it’s been that steady medium that I’ve always been able to tap into to express myself.

Helena Julian

The intent of Get Free, as you write yourself, is to “actively dismantle imagined limitations to liberate body and mind.” How is this pronounced in the album?

Tygapaw

It’s about self-expression, essentially, and my intention was that I wouldn’t limit myself or second guess myself in the process of making this EP. Imagined limitations are projected limitations. As a child, everything is infinite. I will often actively fight against this limiting voice within that knocks you down to size. Especially for Black people, we’re often confronted with what is considered as realistic dreams. Being an artist and touring the world is not a realistic dream, which is disheartening. I am where I am today by overcoming those limitations. Get Free is an exercise in breaking free of limitations that are projected onto you. At the same time, it’s an account of that process. I allowed myself to freely compose based on what was in my head.

Helena Julian

Your work is often fueled by text and poetry. What is the significance of poetry in club music for you? How can we listen to poetry in the club?

Tygapaw

Words carry such a heavy weight. I always think about how words have been used to weaponize abusive behavior. Growing up, I definitely experienced that. When I hear words that are both powerful and empowering, uplifting and affirming, I just have to find a way to inject them into my compositions. That is my response to elevate the listener, perhaps contribute and add something that they didn’t know before. When I collaborate with a poet or a writer, it’s a very powerful process. I’ve collaborated with the artist Precious Okoyomon in the past and have been doing sound design for them. “Black Womxn Experience” was a work I did years ago, and this was my first exploration of using poetry as a medium in my work. I’ve also done several mixes which included texts that have been inspiring to me. I’ve done one with Toni Morrison, Grace Jones, and Nina Simone. Spoken word has been in my practice for a minute for sure.

Helena Julian

The writer and poet Mandy Harris Williams contributed original texts to several tracks on Get Free. How did your collaboration with her unfold?

Tygapaw

As soon as we met, I immediately knew that I’d like to work with her. I felt that working with her was the best fit for the project. I just needed to get the project together and figure out how. I ultimately asked her to be a narrator for the tracks.

I conceptualized Get Free as a story, a journey of someone searching and finding liberation. I got inspired by watching New Dance Show, which is basically a club dance show that was filmed in the late eighties and early nineties in Detroit. I used to watch Soul Train, I grew up watching that. But this was the first time I saw something of that format but set to techno. The music wasn’t pigeonholed into what the Black community would listen to as with Soul Train—this was electronic music, 130 bpm. There seemed to be an untold history that I wanted to find my way back to. I was feeling that connection to the past and realizing that we had been here all along, making incredible techno. I knew about Detroit techno, but for me dance is such a strong element when I create music. I always think about the body.

Together with Mandy we spoke about all these elements that were inspiring me. We were trying to create this world that we could move forward in. She translated my thoughts very eloquently within the tracks, it was a very seamless process.

Helena Julian

The body is also implicit in the texts: we listen to affirmations, thoughts about body and identity politics, and sentences that localize the body in its surroundings. How do you invite the body into the work?

Tygapaw

That happens when I’m creating the percussion elements. Rhythm is in the center of the music, and that is why I was drawn to techno. I felt compelled to explore variations of repetition, all its nuances building in intensity. This is all informed by playing in clubs and seeing what an audience responds to, how their bodies move in a space. It’s like brush strokes on a canvas, that’s how each percussion element translates in space. They work in cohesion with each other. I used to use a heartbeat sometimes in my tracks. There is literally a beat in our bodies. And sometimes I think it’s very spiritual too: I’m unconsciously tapping into something that I’m conscious of. It feels like I’m conjuring something of the past to create something of the future.