Purpose in Cause and Sound Somatic Rituals

Somatic Rituals

Photography

Flavio Karrer

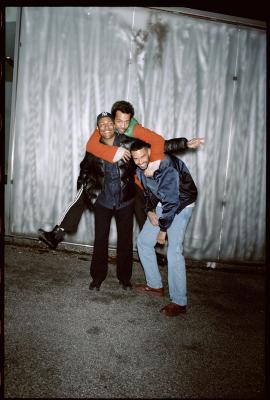

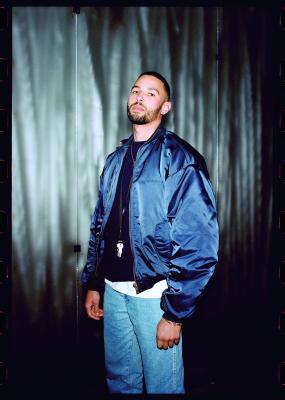

Five years ago, Basel-based artists Mukuna, Kombé, and Mafou collectively released SORI 001, which marked their production debut and initiated the label Somatic Rituals. Since then, they’ve been keeping busy and building throughout Switzerland and abroad with a monthly residency at Basel’s Elysia, a show on EOS Radio [see zweikommasieben #25], and visits to places like New York City to link with like-minded artists and collectives. Since the beginning, Somatic Rituals has been in constant progression, both as a collective and as individual artists, without taking any shortcuts and a belief in a deliberate process. They tackle all of it with an insistence on the premise that excellence in craft and forming community (both on and off the stage) are the bedrock of their endeavor.

With their five-year anniversary approaching, it seemed like the right time to sit down with the collective and have a chat. Coherent, composed, and very much in-tune with what they want to convey, it seems as if both their vision for their label and artistic practice are falling into place. Max Wild asked them about what they’ve been up to lately, the responsibility and pride that comes with being a Black-owned label and what the future holds for Somatic Rituals and their members.

This interview was originally published in issue #27.

Max Wild

I know that you started mixing and producing together, and that you’ve been friends before connecting through music, but how did your first steps in Basel’s club scene come about?

Mafou

We’ve been around a while now, but in terms of putting ourselves out there, we always wanted to feel sure about what we do. We were quite sure about taking one step after the other and really diving into the art of mixing and producing music. I think now we are really taking advantage of the skills we’ve acquired over the last couple of years. I guess we just hung out with the right people at the right time. Basel’s techno scene is very small, but we were always pointed in the right direction.

Kombe

I’d say the people from Alma Negra, Goldfinger Brothers, and Amenthia were significant for us. Amenthia to this day is, and I say that in the most endearing way, obsessed when it comes to mixing and producing. But that is exactly what we needed to see in order to develop a serious approach to this whole thing. It’s not just about being skilled DJs or the capability to dish out bangers. Of course, we also enjoy that at times, but Amenthia had a very earnest approach to creating an experience, to build a sound wall very much in tune with the venue and crowd, and to endure. Not just chasing one climax after another, but building suspense in the moments in between.

Mukuna

I think this approach really is in line with what we enjoy most. At first, lengthy beat matching was a skillset required due to mixing with vinyl, but we enjoy long transitions where the rhythm progresses over time, creating new rhythms within the bridge. At times, it feels ritual.

Mafou

It is really important to us to bring our sound and our energy to every place where we share music. That was a principle from the beginning, and it really helped us by putting our integrity first. Wherever we go, we do our thing.

Max Wild

Is it fair to say that you don’t want to dilute your work and, at the same time, want to create spaces where such practices are the principle, not an exception?

Kombe

Definitely. A couple of years ago, places where you could play a more eclectic set during main time were scarce. That changed the last couple of years, but I’d say it’s still the status quo. Whether you go to Elysia in Basel, or Zukunft in Zurich, you expect a specific sound. Of course, you had your outliers like Longstreet in Zurich, where DJs had room to play a broader array of sound. We always enjoyed that, but we still felt more akin to techno and house music. Now, with our residency at Elysia or our parties at Rouine here in Basel, we are more deliberate with our intentions and the profile we want to carve out. And with these platforms, we can get people on board that not only share the same sound as we do, but also the same experience.

Max Wild

And you seem to be building solid ground in Basel.

Mafou

It’s a process and we are still negotiating and coming to terms with it. We needed to get used to it. I think at times we struggled, because when we were young we thought, “we don’t look like the people at the top.” That messes with your head. It’s nice to hear from people around here and abroad that we are on their radars. From the beginning, we all had very demanding attitudes towards ourselves, and fortunately, that is paying off. Our structure as a collective has become more professional, just because we expect more from ourselves.

Mukuna

That’s why Okra is a sensible addition to Somatic Rituals and vice versa. With Okra and the people involved, we create spaces for Black people. We seize the place; we organize and invite on our own terms. Somatic Rituals is more specific: it’s a music label—Black-owned that is—and our sound is the bedrock. Both collectives complement each other, without diluting the core message.

Max Wild

A couple of weeks ago, you took part in a residency at Kaserne Basel, curated by Forever Imbricated [Forever Imbricated is an artistic platform that promotes the forging of alternative social architectures and the collaborative building of fantasies. Inspired by underground scenes and club culture, Forever Imbricated aims to reflect on how radical forms of togetherness can influence and change mainstream society.] As a part of the Okra collective, you joined forces with Jokkoo collective from Barcelona and DeForrest Brown Jr. from the USA. Your performance-installation was called “Black Atlantic Lifeworld” and was described by Jokkoo as an attempt to “transform the space of Kaserne Basel […] in order to build a bridge between modern Black Aquatic mythology and the reality of the Black cemetery of the Atlantic Ocean.” Looking at the images, it seemed to be both immersive and cathartic. What was your experience like?

Kombe

Well, we didn’t really know each other before. So, at the beginning, it was really just about listening and understanding where we all come from. Looking back now, it was inspiring for what we want to achieve with both Somatic Rituals and Okra: it is not only about sharing an African heritage, but a broader sense of Blackness.

Kombe

Yes, we all are Black. Yet, when we met at Forever Imbricated for the first time, we all had a different understanding of what it means to be part of an African diaspora. All of Jokkoo’s members are firmly entangled with their respective countries and have vivid recollections of their African cultures. Then you have DeForrest Brown Jr. as a representative of the Afro-American experience. It is a culture that deals with a history that is shaped by the transatlantic slave trade, devoid of ancestry, heritage, or language.

Mafou

And then you have Okra: all of us have African roots. We know our heritage and even had the privilege to visit these places through our families. At the same time, we have a much lesser understanding of African cultures than Jokkoo. Our context and upbringings are, to an extent, Eurocentric. It was enlightening to talk about the nuances of African diasporas and the common experiences of the Black body.

Max Wild

The practices of Jokkoo, Okra, Somatic Rituals, and DeForrest Brown Jr. orbit around music.

Mafou

Yes, and we learned from both Jokkoo and DeForrest Brown Jr. We were excited to see how Jokkoo approached the residency. They had a very clear vision of how they wanted to own the place and the outcome of the project. They wanted to be in control of the space and its perception, and that is what we aspire to with Okra and, to an extent, with Somatic Rituals.

Mukuna

Hearing DeForrest Brown Jr. talk about the Black body in context of techno music was truly educational: he laid out how the second wave of techno producers from the early 1990s, such as Carl Craig , Underground Resistance , and Drexciya blended radical Black politics and Afrofuturist mythologies with the mastery of their drum machines. We didn’t only engage as members of African diasporas, but as musicians.

Kombe

As Okra, we felt like the connecting link, because we could relate to both parties. For me, it was interesting to see how you could make connections, without necessarily knowing all the references: a part of DeForrest Brown Jr.’s identity is very much rooted in Drexciyan mythology [Drexciya was an American electronic music duo from Detroit, consisting of James Stinson and Gerald Donald. Alongside their music, they developed an Afrofuturistic mythology with a Black diaspora at its core.], whereas Jokkoo was not familiar with their practice. For Jokkoo, the Atlantic Ocean is a cemetery, where spirits of captured and killed Africans live on—and you could easily draw connections to the Drexciyan myth. We came together, learned from each other, and ultimately, connected the dots.

Mukuna

The next chapter of the Drexciyan mythology would have been to go to space, which makes a link to the Dogon tribe in Mali, who are said to have gotten their knowledge about the Sirius star from extraterrestrial life that visited Africa years ago.

Max Wild

All these transcontinental connections are applicable to the migration of sound.

Kombe

Yes, and to hear DeForrest Brown Jr. talk about the voyage of rhythm and sound from the west coast of Africa to the east coast of America to the shores of Europe was inspiring. It is about knowing and owning your heritage.

Mukuna

And it’s the same with rhythmic patterns in techno, transcending from one continent to another, carrying so much history. All compressed and filtered through machines, which gives it such a contemporary layer.

Max Wild

The same work is being done, possibly even with the same intentions, without knowing about each other, but taking part in different places of the world?

Mafou

Exactly. My dad is a percussionist and an expert when it comes to Senegalese drums. In hindsight, it is what spoke to us the most, also in terms of finding our language in sound. After the experience at Kaserne Basel, we all felt the need to intensify our research. Through knowledge we can own our narrative. This background has become crucial not only for better understanding the sources of sound, but also to have agency. When we pulled up to one of our first radio shows a couple of years ago, they thought we were doing trap music. And we had some shitty interviews. Mukuna had one in Amsterdam just now in February where the interviewer came on and started the conversation with a question about whether he brought his drums, because he plays rhythm-based sound.

Max Wild

Shut up.

Mafou

I’m being serious. And it’s an easy narrative to fabricate. Three guys from African descent, using afro-drums as percussive beats. We noticed that we need to be prepared for these confrontations, because it’s a regular thing. We don’t have a background in art, we are not used to arguing for our work or giving it context. And we want to keep that spirit somewhat alive. We don’t always need to explain our music. Sometimes, I do what my gut tells me, and when it feels good, it usually sounds good as well. That’s fine.

Mukuna

I think really engaging with the source of sound and legacy is to an extent about showing appreciation for the craft we are doing. We could easily market ourselves as three Black DJs, who source their music from their African heritage. But that’s just not it. First and foremost, our sound derives from techno, house, D’n’B, and jungle. But if you don’t speak, people will speak for you. We learned that.

Max Wild

I asked myself recently if it’s even possible to remove yourself from the political discourse as an artist nowadays?

Mafou

As a person of color, my skin itself is a political statement. But if you are white passing, you probably can. This encapsulates what we just talked about: we feel the need to be in control of things, both as artists and as persons of color.

Mukuna

This sensitized us in many ways. Obviously, you can’t control the public discourse, but we can control what we put out there, how we do it and through which channels.

Mafou

That is why for “Black Atlantic Lifeworld”,we collectively made the decision to wear white suits, with the intention to remove the focus from our Black bodies. In contrast I remember our first experiences in club culture quite vividly. Around here in Basel, we were, more often than not, the only three Black people on the dancefloor at this very specific intersection of techno and bass music.

Max Wild

It seems like you have a clear vision, both for Somatic Rituals and Okra. So, what’s next?

Mafou

As Mukuna said, we are a Black-owned label, and we want to keep it that way. We feel a responsibility, which we carry with pride, because we feel that we are in control of where or whom the spotlight shines on. And that is by no means just political. With Somatic Rituals, first and foremost, we want to represent good quality in terms of creating and mixing music. That’s where it all began, and we don’t want to diverge from that.

Mukuna

We really want to push the needle in what we do with both Somatic Rituals and Okra, but it has to happen with integrity. We are playing the long game.

Mafou

Thinking back to coming up in Basel’s music scene, we are very thankful for the people who offered guidance. We’d like to offer platforms where encounters are encouraged, where we can link and build together here in Basel and Switzerland. At the same time, we always took inspiration from our gigs abroad. We just played in New York in January at Andrew’s [Akanbi] “Groovy Groovy” party, and the scene there has such a relentless drive and commitment. It’s rewarding to branch out, carve out new relationships, connect through music, and implement all that input into our own practice. More than anything, we want to keep challenging ourselves.

Mukuna

Working together artistically but also being friends is never easy, because the process of it all is so personal. But we all find our ways to contribute and understand each other. We are having fun and I find it deeply satisfying to work together and see each other succeed.

Max Wild

And you are doing all that while still pursuing your own paths. Kombé, you mentioned your upcoming EP before we sat down. How is it coming about?

Kombe

I’m almost there, finishing touches. It is a very personal experience, just because I have the final say. Of course, I often reflect on my work with Mafou and Mukuna, because I appreciate their thoughts. But still, this EP will represent me as an artist. I feel that now, with all the experiences I gathered, I have a very high standard in terms of sound design. I want the rhythm to be fundamental, without playing into any suggestive stereotypes we talked about before. To an extent, it’s a contemporary document of what I listen to, what I like to play in clubs and what I am thinking about now. Yet I want it to be timeless, which is a trademark for the sound we do.

Mafou

I am going out on a limb and say that we could’ve released our tracks ten years ago and they would have had the same resonance and meaning.

Max Wild

When you say that the EP is a distillate of you at this time and moment. What are you listening to and what are you playing?

Kombe

I noticed that I am distancing myself from genres more and more when I am digging or looking for inspiration. Instead, I am looking for tracks that are so reduced that I am able to collage them together into a set consisting of techno, house, reggaeton, whatever. By rhythm, I also mean a certain timbre, which then again evokes fluidity and drive that carries through our sets. I want my EP to be the same: fluid and ongoing.

Comments

1 DeForrest Brown Jr. contributed quite some pieces to zweikommasieben, for example essays on Dawn Richard or Lonnie Holley, or an interview with Eartheater.

2 A topic discussed by Soraya Lutangu Bonaventure in conversation with Bobby Kolade.